NOTE: I’ve been going through many years’ worth of blog archives, finding pieces I’d nearly forgotten about—those little gems that meant something to me when they were written, and, it turns out, still do. This is one of them.

I do this from time to time, and I recommend it for all writers with stories they’ve written long ago. Pull them out. Share them. Don’t leave them in the dark when it’s sunlight they need.

You’re not letting your readers down by not producing new stuff for them all the time. You’re giving them a gift. If you love it, release it. Let it breathe again!

My grandmother, Lydia–my mother’s mother–had two babies out of wedlock before my mother and her three siblings were born. I didn’t find this out until they were all long gone. I’ll never know if my own mother knew this and kept it secret, or if she was as clueless about it as I was. My sister-cousins knew nothing, either. (There are three of us, born of Lydia’s three daughters, and we’re more like sisters than cousins.) We found ourselves mourning babies we didn’t even know existed. We cried for our grandmother and loved her even more.

My Finnish grandmother was loving and funny and wise. She taught us Finnish songs and made silly jokes and told us stories in her broken English–but never about herself. If we asked, her stock answer was, “Oh, nobody cares about those olden times.” We did care; she wouldn’t budge.

I learned about her babies some time in the mid-80s, when I spent a week alone in Michigan’s Copper Country—the place where generations of Finnish relatives, including my grandparents, my mother, and me, had been born—researching a book I’d received a grant for and was working on (but never finished, in case you’re wondering). It was about the 1913 copper mines strike, a prolonged, often bloody event that had been written about often, but not in novelized form and not about specific families. The men and women in my own family had been directly involved, and it seemed I was at a stage in my writing life where I might be able to do justice to their stories. Turns out I couldn’t, and except for a few chapters I’ve kept, it’s been abandoned.

But there I was, in the early 1980s, in those same locations, using part of my grant money to spend some time there researching at Michigan Tech’s archives and talking to the few people I found who still remembered those events of 1913. At dinner one night, my great-aunt, one of only two living relatives left up there, moved away from the mine strikes and dropped the bomb about the babies my grandmother had lost. It was out before she could stop it and she thought she had said enough, but I reminded her that anything she told me then was beyond hurting anyone.

Women in those days had miscarriages all the time, but these babies lived beyond infancy. They had names. They had the same father, a man who was not my grandfather.

I prodded, and my great-aunt finally told the story: My grandmother was young and unmarried and had been raising her two babies while living with her parents. They lived in a small town with more than its share of small-town gossips. I tried to imagine what it must have been like for her, keeping and loving not one but two illegitimate children, and then losing them both to a scourge my great-aunt only remembered as “awful diarrhea”. She didn’t remember the children, but my great-uncle told her he had played with them often and was heartbroken when they died, one after the other.

I went to the county courthouse to look for their records and, in spite of the efforts of a kindly clerk, only found one. The father’s name was right there but nobody I talked to knew who he was.

The cemetery where my great-aunt thought they might have been buried is old and grown over, with only a handful of headstones still standing. The burial records had been lost in a fire a half-century before I began looking. Their markers would have been made of wood and were long gone, if they ever existed.

When my week was up, I left the Copper Country and still the mystery haunted me. I drove the 600 miles back home alone, and along the way a poem wrote itself:

Looking for Lydia’s Babies

There were six of them, not four, and I was told this

in the year she would have been one hundred.

The teller gave the news in muffled blasts

Wrought from years of keeping this thing quiet.

The two who came before the ones we thought were first

Were shadow babies born before their mother wore a ring.

They lived beyond the infant stage; the teller knew their names

But how they lived and when they died she could not say.

She only knew that they were mourned.

A boy and girl, but who came first? Only Hugo had a life

According to the courthouse records.

He even had a father.

But Esther, loyal Esther, kept her secrets

While her mother held us close and whispered hope

And never told us that two more had come before.

Their mother could have passed this chunk of history on.

We begged for hints of just what kind of girl she was.

And all she did was sing another song.

Maybe all we wanted was for her to laugh, to sing,

To check our fears

And rock us on her ample lap.

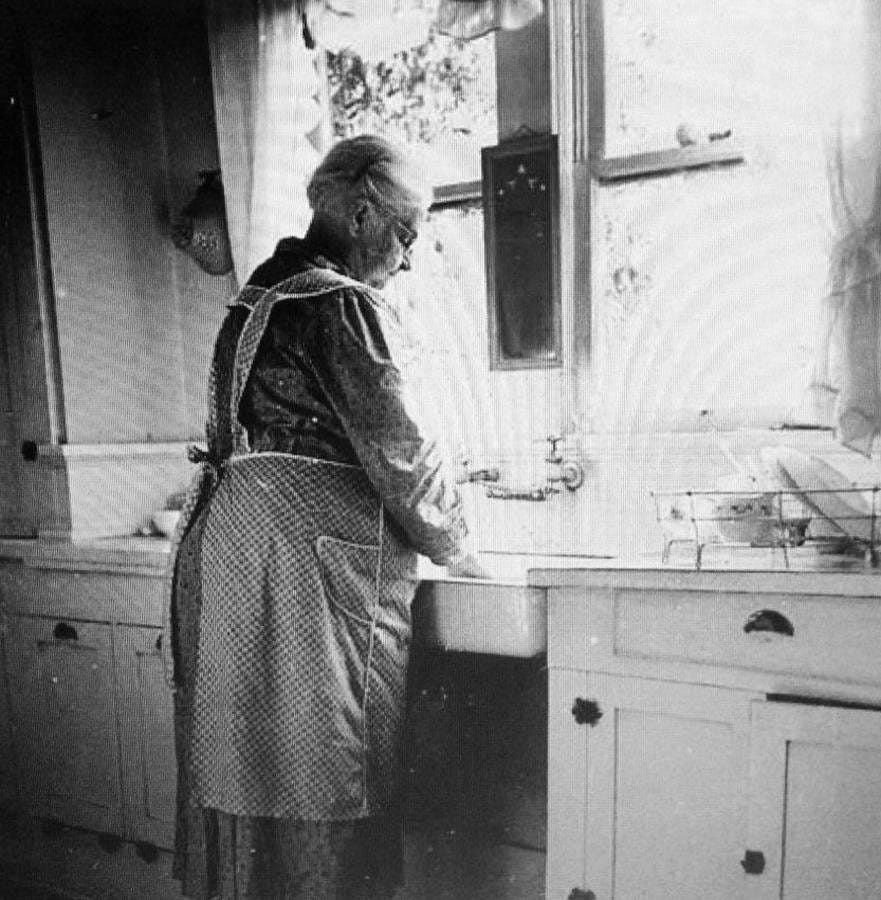

Maybe even, summers, when we helped her bake and scrub

She opened doors that we ignored

Or didn’t want to see beyond.

But later we were modern women, guilty of our own transgressions,

Reeling with our own confessions.

Open to the story of those babies.

And still our grandma could not speak of children left behind

In unmarked graves asleep beneath their quilts of creeping myrtle,

Waiting for their kin to call their names.

I wanted to talk a bit about the cadence of my poem. It's sing-songy, as if it could be spoken with a drumbeat. I didn't realize it when I wrote it, but I know now there's a reason for that.

The book I was writing at the time had references to Finland's epic poem, The Kalevala. I read the entire book, some 23 thousand verses, and did a lot of research about the origins, the characters, etc. I immersed myself in that poem, reading everything I could get my hands on, and I didn't realize how much the cadence stayed with me.

The Kalevala was spoken before it was written, and the Rune singers who memorized it and recited it, did it with accompanying music--on a kind of lap-harp called a Kantele. When they weren't strumming it, they were banging on it--like a drum--each hit as emphasis to the spoken line.

It's said that Longfellow saw a performance of the Kalevala and used a similar cadence for "Hiawatha". You can hear it in those first lines:

On the SHORES of GITCHE GUMEE,

Of the SHINING Big-Sea-WATER,

Stood NOKOMIS, the old WOMAN,

POINTING with her finger WESTward,

O'er the WATER pointing WESTWARD,

To the PURPLE clouds of SUNSET.

I didn't write to a beat on purpose, or even consciously, but it seems to fit. I doubt if I could ever do it again.

(I've read, too, that Tolkien was influenced by the Kalevala, and there is that kind of drumbeat to some of his passages, so it could well be.)

Beautiful poetry. A prayer for Hugo & Esther. Maybe finish the book?